Algorithm II: Memetic Filmmaking

What happens when The Algorithm drives production?

Disclaimer: If you have not read my post on Netflix and The Algorithm, I advise you to at least skim the intro and conclusion, as this post, the second in the series, will build off of the analysis I performed therein.

Stranger Things premiered in 2016, and I immediately thought it was pretty great. It reminded me a lot of Super 8, sure—I didn’t think it was particularly original, I suppose, but it was an entertaining take on a genre that I had passing familiarity with through cultural touchstones of the 1970s (and their contemporary homages). The cast was fantastic, obviously, and the visual language of the show was deeply compelling; I still tear up every time I see the Christmas lights begin to illuminate. Overall, I loved it, and I was excited for more.

Well, there was one thing…did the showrunners not know about binge-watching? This question occurred to me around the third time I was shown the same flashback, to a scene I had already watched that same day (because I was binge-watching). It really felt like the people making the show were not quite ready to adapt their filmmaking to the new model of film consumption—which was starting to become widespread around that time, though it was certainly not new (and definitely not new to me, since I had been binging shows since the first season of Lost came out on DVD, a decade prior). Or perhaps they were just trying to engineer a cultural touchstone from a piece of media that was too young to have earned that status organically…

In 2012, Disney acquired Star Wars—and I felt my stomach drop. I was not sure yet what I thought the consequence would be—this was Disney, the singular author of my early childhood, so why shouldn’t I be excited for them to unite with Star Wars, one of the dominant coauthors of my preteen years? Well, I wasn’t—but, lacking any ability to articulate why I wasn’t excited, I simply watched. And waited. I waited through the release of The Force Awakens, a movie I loved, which a lot of people seemed really unhappy with. I waited through the announcement of Rogue One, which seemed to be both a Star Wars movie and not a Star Wars movie. By the time I walked out of Rogue One, however, I had an explanation, and it was, oddly, related to Stranger Things…

In 2015, I went with my friends to see Avengers: Age of Ultron in the theater. I remember nothing about the movie, even though I have seen it at least twice since. What I do remember is that I’d started to wonder where the heck they were going to take the series next. I don’t mean that I was curious about the story presented to me—no, I was curious about the metanarrative, the story of how Marvel had grown as a cinematic brand since the self-referential credits sequence on the second Spider-man movie1. Bringing all those superheroes—all those disparate narratives and ideas—onscreen in one epic crossover2 felt like the culmination of the Marvel story. I could imagine some options for new stakes, new narrative paths—but none of them seemed particularly good…

Finally, in 2016, I was riding in a car with a friend, and I took a stab at synthesizing these three threads, blurting something to the effect of, “Disney is going to ruin Star Wars just like they ruined Marvel, and I know this because of Stranger Things.”

First, A Definition

Memetic Filmmaking is a term I coined c. 2016 to describe aspects of a film’s narrative and production that exist either in emulation of, or to facilitate, Internet memes. It’s that simple—and, of course, much more complicated: memes were booming by that point, and they served as a form of marketing for the content that begot them, embedding the source material deeper into the cultural consciousness, ensuring the media was consumed by the broadest possible audiences. The complicated part relies on the definition of meme; a (semi-)literal meme is an image or bit of text, but there is an argument to be made, as well, that meme is the language of The Algorithm—both the base code and the output of a logic designed to flatten and combine as much as possible, to maximize the potential user base.

Remember when gifs were good? You could find a gif for literally any scene or quote you could think of—unlike now, when image search has been eviscerated by rights management, and everyone uses the same three gifs. To my mind, this is The Algorithm: serving up the popular gifs as suggestions, so only the popular gifs get used—then used again, and again—while the rights-holders quietly rendition their proprietary content.

To make this easier, I am going to identify three aspects of The Algorithm that I see as drivers of content. Although all of these are, as far as I can tell, present in the three franchises I am using as my cases, I will associate each aspect to only one piece of media, using the expectations of The Algorithm as a framework to understand the creative choices we see onscreen.

A successful meme is self-perpetuating; a self-perpetuating meme will be successful. Do you know why you should press F to pay respects? Good news: you don’t have to!…as long as you add another ‘F’ to the comments. The algorithm must be fed, and it feeds on engagement. The audience must be fed, and the algorithm feeds it content. This is a closed loop—a meme gains popularity through being used, and by being used, it gains popularity, which can be substituted for context.

No potential subscriber left behind. The widest possible audience is less goal than imperative—every person who is not subscribed is a revenue stream your platform is missing out on. I’m actually not interested in doing a whole post about how I predicted the streaming wars in 2010, but I think the subscriber model underpins this facet of The Algorithm: more fans => more subscribers => more revenue.

Nothing new, EVER. The SEO doesn’t know what to do with a wholly novel thing—what tags to give it, what content habits it might be associated with. Every piece of content should build off of, invoke, hearken to, provide backstory for, etc. an existing piece of content (preferably another one produced by the same platform). Crossovers, franchises, and nostalgia—the dominant forms of media nowadays—are all anchored by association to preexisting touchstones.

As may be self-evident, these three aspects are inextricably linked: new spinoff content is released, and existing fans disseminate it in bite-sized chunks through social media, which brings in more subscribers, who demand new content building off of the existing content they subscribed for. So even though I will be separating these phenomena a bit to discuss their observable effects, we should keep in mind that the larger ecosystem is still running in the background.

Finally, any time I say The Algorithm, I am, of course, referring to the multiple algorithms that drive content and engagement across many different platforms—but along parallel paths, operating by the same principles.

A Successful Meme

Jenny Nicholson’s video, “Oh no! The Rise of Skywalker was real bad :(” is one of my favorite bits of comfort-watching—she says so many true things in it, which feeds my soul. Her analysis includes the following quote:

“I feel like if, before this movie, you showed me a list of things that happen in the movie, I’d be like, ‘Okay, this sounds like a movie I would want to watch.’ But if you showed me a list of things and said, ‘This is the movie,” I would say, ‘What? No this isn’t! This is just a list of things!’”

I appreciate the irony of using this quote in my Marvel section, but I just find it too apt: it precisely describes how I have felt about Marvel movies for a very long time. Look, I was with everyone else. I was excited when Nick Fury showed up at the end of Iron Man, wondering what might be possible, with Marvel gathering its various properties into one studio.

The thing is…the movies weren’t consistently good. Neither were the shows. Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. was actually rather boring (while Agent Carter was tragically ahead of its time). I watched the first Thor movie and decided that was enough Thor for me—I didn’t see a need to bring all of that gods-and-mythology nonsense into a series of stories that were mostly about scientifically-enhanced humans3. I had never been quite as entranced by Superman or Wonder Woman as I was by Spider-man and Iron Man. Myths and magic seemed like it had the potential for a whole lot of genre creep, and I liked the genre the way it was.

But then the crossovers did start happening—and I was even less enthusiastic. Iron Man is a movie about rejecting the machinery of war, including the private companies that profit from it and the political entities that propagandize it. Even Tony Stark declaring that he is Iron Man supports that theme: in a world where you can never be sure who the true enemies are, his transparency is a rejection of the corruption that harbors warmongers and bad actors. Captain America: Civil War, on the other hand, is about…watching your parents fight? The conflict that drives the Avengers apart is less compelling (and less generating of buzz) than the optics of the heroes duking it out in a cheap “Who Would Win?” matchup. I find it tacky, and uncomfortable—and deeply unnecessary.

But it is necessary…because by the time Civil War released, the point of Marvel was less to tell compelling stories and more to hold up a list of heroes and say, “This is the movie.”

I used to attend Broadway shows pretty regularly, and, in 2018, I noticed this horrible practice was becoming fashionable among Broadway audiences. If a famous person, such as Bernadette Peters, has a role in a popular show, such as Hello! Dolly, the person’s entrance onto the stage is greeted by a round of applause that lasts several minutes (and may even include a standing ovation). I find this appalling—besides letting every actor know that their performances are not all appreciated equally, it fully stops the show for several minutes, usually at a point where the show is not designed to stop. And for what? For the audience to break the Fourth Wall, acknowledging that this role is only a part in a play, and the actor performing it has meaning outside of the text.

Now, when I watch a Marvel movie, such as Avengers: Endgame, I kind of imagine the whole audience pausing the movie to applaud every time it cuts to a new member of the ensemble. Well, not every member of the ensemble—we know, of course, who the real stars are. Did The Falcon need to have a cameo in Ant-Man? Will anybody watch a Spider-Man movie if Tony Stark isn’t in it? Is any Marvel movie worth watching if it doesn’t have Iron Man? Clearly, Marvel is not confident they will.

No, Marvel is operating on the assumption that pointing the camera at a bunch of big-name superheroes can substitute for plot, theme, character development, etc. There are strong films within the MCU, but they tend to hinge on the association of big-name directors, who are swiftly becoming memes in their own right.

For what it’s worth, I called it quits when I saw Doctor Strange 2 in the theater. The man who first inspired my love of Marvel returned to the director’s chair, and put out a film anchored by an absolutely disgraceful story. Not only did it “resolve” the arc of WandaVision by simply resetting the character of Wanda to her pre-series psychology (begging the audience to wonder what the point of WandaVision even was), it also included an extended cameo sequence for characters I didn’t care about, because I was already starting to fall off the rigorous consumption schedule Marvel requires.

The thing is, I will continue to see Marvel movies, if I hear that they are good (from sources I trust). But that is not the content strategy—that is a failure for The Algorithm. The Algorithm put this disastrous storyline in Doctor Strange 2, so I would watch WandaVision. To The Algorithm, it shouldn’t matter whether the story of either work is good—the only thing that matters is that I consume one, so I will be forced to consume the other, so I will want to consume the next thing. And so on. It is a content machine, engineered to keep me paying for Disney content.

And…it works! It didn’t work with me, but it does work (and other things work with me, so no judgement). I have spoken to people who enjoy this content—who continue to consume any and all Marvel content, regardless of quality. The strategy has become a standard because it works.

I think I understand why, too: it feels good to the brain to connect meaning, even if it’s just the tiny hit of dopamine from a single, unmoored touchstone. “T.A.H.I.T.I. is a magical place”—I don’t quite get chills, but I do still get that little Ooh of dopamine, telling me, Yesssss, there’s a connection—connect more things! More Iron Mans! It feels inherently good to examine two disparate pieces and see the connections between them—the same way it feels good to pick up on an Easter egg or puzzle out a wordle or realize that a cliché has meaning.

But these clichés are sacrificing meaning: no matter how good the Doctor Strange films get, watching them will never feel as satisfying as watching, say, The Lord of the Rings. The story being told has been compromised for the sake of holding up the various memes. I think that The Algorithm also wants this…after all, isn’t this the governing principle of TikTok? Why would The Algorithm want me to watch a three-and-a-half hour movie, when it can make more money off of getting me hooked on three-and-a-half hours of content variety, each little bit of which suggests a whole other content pathway I can embark upon (and offer my time, my money up to)? Short form content is just a natural outgrowth of a platform-based content strategy, churning out new memes to hook new subscribers…and so on.

Because I am juggling rhetorical tasks, I just want to take a few words to explicate this observation in terms of my thesis, about memetic storytelling: Memetic storytelling requires you to devote a certain amount of story space to elements that are ultimately meaningless to your narrative4. Whether it is an inconsequential cameo, a story beat for a different story, or a symbol that is thematically dissonant, you are taking away from the story to advertise other content. It’s product placement, and it cheapens the final work, even if the product you’re advertising is more of your content.

Size Matters

Since I began the section on Marvel with a quote about Star Wars, I suppose it’s only appropriate I begin the section on Star Wars with an article about Marvel. In the persistent page for my sources, I linked a fantastic article, “Everyone Is Beautiful, And No One Is Horny”. Given how much of my process I have already enumerated, I’ll skip to the synthesis: at some point, I encountered an analysis of why no one is horny in the movies anymore: depictions of sex reduce the potential audience size for a given film. At some point along the way, audience size became the single, undifferentiated standard which all blockbuster media was trying to uphold.

I mentioned in my intro that I believe this is tied into the notion of the subscriber model, and I will expound a bit on that here. When Netflix began streaming, their business model was based entirely on subscriber revenue. When they started producing shows, their content was extremely high quality, because they were trying to compete in the era of Peak TV. That was when a question formed at the back of my mind: if there was a point of subscriber saturation—if, for example, every single person on Earth who had an Internet connection and an extra $100/year to spend on entertainment had a Netflix subscription—, would that produce enough revenue to support their content output?

The answer is just no. Making shows is expensive—and that was before every studio decided that actually they wanted to reclaim the rights to Netflix’s existing library (or wanted more money from Netflix to hold on for another ten years5). We, as a society, have only found one way to finance quality television production at scale, and it’s advertising. Even if you force individuals to own their subscriptions (sacrificing your best marketing tool—and some revenue, I imagine, as you simply force would-be subscribers off the platform because they can’t pay…yet), there is still a ceiling.

I know Netflix sensed this issue, sacrificing prestige for a greater variety of “original” content in a thirsty bid to expand their subscriber count—but this section isn’t about Netflix. It’s about Disney, and their purchase of Star Wars.

The original Star Wars movies were, in my opinion, hastily plotted and only lightly themed, substituting archetypes for any original storytelling insight. They’re technical marvels, sure—but the storytelling is weak, relying on the viewer to derive meaning, based on existing assumptions. Then The Last Jedi came out, and suddenly there was a sharp split in the dedicated Star Wars fandom: depending on which statistics you look at, Disney would lose between one-third and half of its Star Wars viewership by committing to a side in the debate. So they didn’t: they brought back universal crowd-pleaser and reliable nostalgia miner J.J. Abrams to produce a finale that was less story and more list of things.

I am going to write a separate post breaking down the role nostalgia played in all of this, reminding you, for now, that all of these phenomena are intertwined. Star Wars relies heavily on the nostalgia of generations for whom the original trilogy and the sequels constituted first contact—but they have not been the only audience Disney cultivated since purchasing the franchise.

Through Clone Wars and Rebels, Disney expanded the audience to children who were too young for the sequel trilogy. Through Galaxy’s Edge, they expanded the franchise to Disney adults with money to spend on experiences. And through The Mandalorian, they expanded it to include all straight women who have eyes (plus more kids—even ones who were too young for the movies or shows, but who were old enough to sleep safely alongside a Baby Yoda6 plush). For those dirty TLJ stans, they even tried to keep us in the fold, allowing Andor to tell a real story, with serious stakes and thematic weight, just so I wouldn’t cancel my Disney+ subscription.

I believe that Disney has effectively enmeshed the constituent works of the Star Wars franchise, such that the better stories provide some amount of scaffolding for the weaker narratives. I have mentioned it before, but I generally don’t have much to say about the original Star Wars trilogy as I do about other films in the series—or other, better films in general. I know there are people who have a lot to say; as I understand it, from people who are deeper into the franchise than I am, that discourse is generally predicated on a holistic understanding of how the original trilogy works together with the prequels and the shows. In other words, they find meaning in movies I consider narratively flat because they derive at least some of that meaning from other, related narratives.

In this way, reach is also self-perpetuating: a baby sleeping with a Baby Yoda plushie—we’ll call him Tommy—grows up watching the original trilogy, along with every story that touches Luke’s narrative. Maybe Tommy shows the sequel trilogy to his friend Braden, who doesn’t have a worn-out Baby Yoda plushie in the corner of his room, insisting that to understand it properly, Braden reeeeeally needs to watch The Clone Wars, which is only available through Disney+. Now Braden’s household has a subscription—and Braden has siblings, so you’ve added five new fans through one toy, bought for a child who was too young to see any of the Skywalker Saga in theaters. Granted, there will be other Star Wars tentpoles in theaters by then—and those need to include images and characters that hearken back to the Skywalker Saga—not to mention The Clone Wars—, for Braden and his siblings. And once Braden’s kids see those touchstones, which can’t be appreciated, reeeeeally, without watching The Clone Wars, well, that’s five more Disney+ subscribers.

But wait…you have Braden’s siblings’ kids, Braden’s siblings, Braden, and Tommy watching the same media across multiple generations. How do you make sure that media is still relevant—not to mention appropriate for kids from 1 to 92? Easy! You make the content as inoffensive as possible, with the blandest possible messaging. Your themes can resonate—but they have to resonate with everyone, so they should be the broadest possible themes, near-universal within the human experience. Your imagery should be palatable, and never dated. The jokes should be politely humorous, taking as few risks as possible. There is no sex, no gore, and no cursing.

I see this discourse sometimes, about whether a Star Wars movie will ever have a sex scene—and I just have to chuckle. Of course not! You could only put a sex scene in there if you were making a movie for adults—and the Star Wars fandom should never be limited by something so broad as age. And if, let’s say, an individual director decided to take a wild swing and make a Star Wars movie just for adults, that movie could not be essential to understanding other stories within the franchise—which would make it nearly impossible to promote (not to mention that it would be a waste of promotional resources, with its limited growth potential).

With this, I am ready to articulate a second trait of memetic filmmaking: No element of the story or production should categorically limit its potential reach. Broad, vague, palatable. Subtlety is out of the question. The Death of Nuance. I believe you can even see this strategy beginning in the prequel trilogy: Jar Jar Binks is out (or very much sanded down, nerfed), and succumbing vaguely to evil is in. A studio can make a fine movie without violating this principle.

But that movie will want for something to say.7

Repeat Stuff

So I have now spent several thousand words describing longstanding properties that were both acquired by Disney. It would be tempting to conclude that this is a Disney problem—indeed, Disney is a good case because they are a content mill with outstanding vertical integration, controlling distribution not only for their media content, but for the merchandise, experiences, services, and theme parks that content generates. Stranger Things season one (yes, I can do this while scoping the Stranger Things part just to the first season) sits at the other end of the spectrum, being an original story produced by a spry new studio with startup cash still to burn.

Surely they can’t speedrun themselves to meme status.

Recall the third driver of The Algorithm:

Nothing new, EVER. The SEO doesn’t know what to do with a wholly novel thing—what tags to give it, what content habits it might be associated with. Every piece of content should build off of, invoke, hearken to, provide backstory for, etc. an existing piece of content (preferably another one put out by the same platform).

Remember (it is OKAY IF YOU DON’T) when I said that Stranger Things uses too many flashbacks (earlier in the post, not in that article for GameRant)? Why would you show us the same scene multiple times in the first season, as if we might forget what we saw three hours ago? Why would you repeat key phrases and images ominously, as if they should have some meaning beyond the text we are currently reading? Why would you have a post-credits teaser?

Unlike Star Wars and Marvel, Stranger Things has no established canon to draw from or hearken back to—so it made its own, as quickly as it possibly could. But the strategy goes further than just hearkening back to earlier in the same story. I mentioned briefly, in the first section, how recognition and repetition hit the brain—these are powerful narrative tools…but they are nothing next to nostalgia.

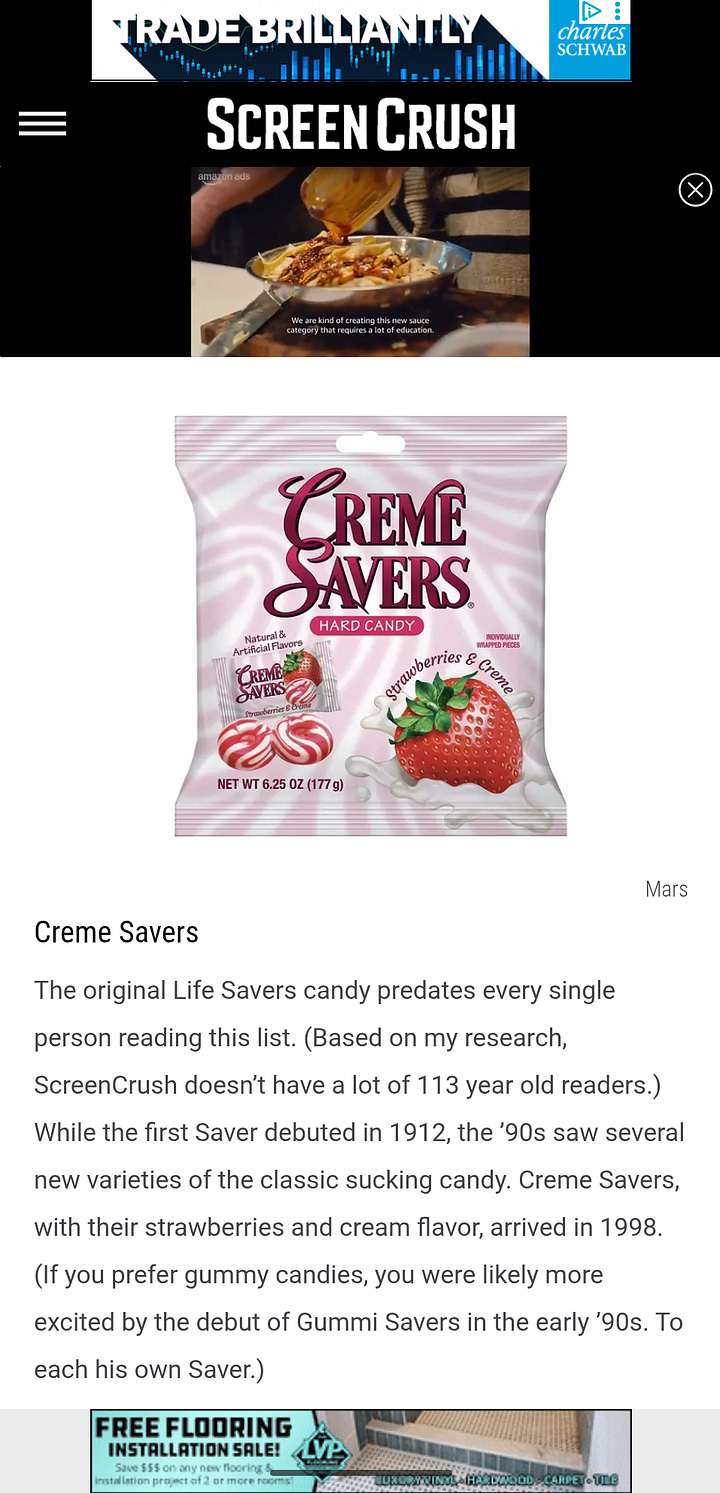

Rather than building off of an existing story, Stranger Things builds its audience connection on nostalgia—and boy, does that work. If the normal function of your brain is reading…James Joyce, let’s say…then a nostalgia-soaked show depicting a period-perfect recreation of your youth is straight heroin. You don’t need to spend three hours investing in a character’s arc; there’s a pachinko8 on screen!

I’m going to pause here to make sure we’re all on the same page: The Algorithm wants your nostalgia. You don’t need to have watched Stranger Things (or any movie, ever, really) to understand this—you need only have spent two minutes googling a handheld Barbie pinball game, and you will have seen ads for seventy-two buzzfeed listicles with foods you can no longer get in stores and Things the New Generation Thinks Make You Old. The taste of PB Crisps is a mere memory for me—but The Algorithm will produce an entire TV show engineered to make me savor that memory just a few minutes more. It knows I can’t ignore every ad on an article by one would-be journalist who remembers them too—not if there are seventeen ads in frame, at all times.

This is the Internet, and the Internet produced Stranger Things. The show is so nostalgia-heavy that there’s scarcely runtime left to tell a story. Funnily, it actually manages to expand its audience by appealing equally to the nostalgia of people who lived its world and the nostalgia of their kids, who grew up watching the movies its world begat. The story, like the setting and the scene, plays on the nostalgia of people who remember The Goonies, Stand By Me, It (the book), and E.T.—even the viewers who consumed that media long after it was popularized. By golly, I bet it played on the nostalgia of J.J. Abrams.9

The part of this I most take issue with is the story. I am not less susceptible to nostalgia than you—and I do not begrudge you your pachinkos and your ubiquitous sexism. I can live with a few extra flashbacks and some odd repetition (though I might point you to Noah Hawley, and the creative potential of adaptation10). But you better fucking tell me a story that honors what the period you’re so nostalgic for actually produced—something with depth and resonance and…nuance.

There is no nuance in Stranger Things (season 1), because nuance is antithetical to virality. The audience is being force-fed symbols and memes to Tweet and talk about (and buy handmade merch of); they can’t also be expected to track the development of motifs through the eight-hour text. Any time spent parsing the story for meaning is less time browsing Etsy for a Chistmas-light pillow, made only more beautiful by the black streaks of an alphabet. That alphabet means something. And the text is going to explicitly tell us what.

Which brings me to my final trait of memetic filmmaking: Symbols must be explicit, relatable, and maximized for SEO. The audience must be told what symbols mean, because the symbols haven’t had the time to diffuse organically through the culture—to permeate naturally, and gain meaning along the way. We are engineering symbols for The Algorithm to reproduce, so we must drape meaning onto them and let The Algorithm fuse meaning and image together. Let The Algorithm make meaning into truth. Let The Algorithm manufacture truth.

Memetic Filmmaking condescends to you, so The Algorithm can exploit you. The filmmaking style preys on your nostalgia, so The Algorithm can feed off your nostalgia. Memetic filmmaking explains symbols to you, so the Algorithm can offer you depictions of those symbols to plaster your apartment, while explaining those symbols with more words. Memetic filmmaking makes associations for you, so The Algorithm can direct you to message boards, where other viewers want to suggest different associations, which are not supported by the text at all.

Why?

You can’t be asking that. Stranger Things is a gosh darn juggernaut, netting subscribers in the…well, we can’t know what numbers, because Netflix has 100% data opacity (and that is nOt aT aLL a red flag). And plenty of viewers, myself included, tolerated subpar sophomore and junior seasons, only to be graced with the sublime payoff of season 4 (I also wrote an article about that). The strategy succeeds because it works.

And now, it governs the Internet…and the LLMs trained on that Internet. Which is what I will discuss in the final post of this series.

A Moment in Narrative History

I have, as I said at the top, been thinking about this topic for about a decade. I am writing about it now because of the AI discourse—but The Algorithm has been slowly compressing cinema that whole time, reshaping our most pervasive artistic medium around its needs. One of the essential precepts of narrative media has already been discarded: a good movie no longer starts with a good story.

In trying to figure out how to wrap up this discussion, I thought of a lot of movies I have seen in recent years—many of them were guilty of the sins I have identified, but they have also pushed me to change my rubric for assessing what a good movie is. Does a good movie need a good story? Yes. But can stories evolve, perhaps, to accommodate The Algorithm…? Maybe.

The Algorithm does not exist independently of culture—the people who consume content also shape it. Perhaps we are in a period of transition, as the Western idea of narrative morphs from a fixed curve to something more fluid, less linear and chronological and narrowly scoped. Perhaps the phenomena I observe are only the awkward outputs of that transition, as the new storytelling devices are shoved haphazardly into the old narrative traditions.

Perhaps.

But I do not want to let The Algorithm entirely off the hook here—I want to talk about those other cultural forces separately, I think, but I don’t want to make the mistake of characterizing The Algorithm as a passive participant in the content ecosystem. The Algorithm is not simply giving the people what they want; it is influencing what they want, by promoting what it thinks they want—and suppressing everything else.

Perhaps more importantly, the people who cater to The Algorithm are participating in its crimes: studios that make bland, broad, meme-based content are enabling the worst harms of an indifferent virus. Franchises, crossovers, and remakes11 did not become the dominant forms of storytelling merely because The Algorithm favored them—they became dominant because content producers valued the financial potential of The Algorithm’s favor more highly than they valued the creation of good art.

Then again…has art not always been limited by financial considerations? How is Lord Disney12 different from the patrons of Shakespeare? How is Netflix worse than the studio system, and the evils it begot? How is catering to multiple generations worse than catering to the Production Code?13

I think the answer has to do with the speed at which content is produced, and the way flaws are iterated through the content ecosystem at all levels. And that is what I will discuss in my fourth post for this series.

Even though Spider-man 2 predated the conglomerated MCU, this bit of self-reference felt BIG. I have never read any kinds of superhero comics—but I knew comics nerds, and I have always been interested in the history and how it plays out through multimedia.

Actually, this is probably about the time that “crossover” started to feel like a dirty word for me, since The Flash seemed to be doing so many crossover episodes with Arrow. Wildly, this post will not have time for that entirely relevant tangent, but I’ll summarize here that I believed they were using the relative critical and commercial success of The Flash to try to increase its predecessor’s profile (even though Arrow was more established, it had significantly weaker writing)—much in the way that Babbity Kate describes the Disney princesses operating, in this video. The Disney princesses, too, are quite relevant to the discussion I am about to have, but I lack both the time and familiarity to expound on that particular franchise; if you are interested, you should watch Kate’s video. UPDATE: I won’t be able to avoid talking about this, I realized, but it has to be a separate post.

There are thematic reasons for this, but I will save those for…well, I don’t know if I’ll ever talk about the purpose of superheroes in culture—but that encompasses the reasons.

I am going to talk more about it in my next post, but this Tumblr post (which I included as one of my key sources) was essential to my understanding of how this principle operates at the visual level, as well as the story level.

There was actually an entire period where I could search for a show I had previously watched on Netflix, not find it, and find it on Hulu—as Hulu snapped up all those licenses during its growth period. The entire CW catalog switched, seemingly overnight, from Netflix to Hulu.

I know that it’s not Baby Yoda—and I don’t care. That’s what the Internet called him for the entire duration of my time caring about the show (which I stopped watching because it was bland, broad, and unmemorable), so that’s the name I use.

I said in the previous post in this series that all of this relates back to my discussion of AI, so here is the post link for that. There’s simply not space to do that analysis in the body.

A pachinko is not featured in Stranger Things, as far as I remember—but it’s a cultural artifact that I actually have direct knowledge of, as well as memories of the way my gen-x family members reacted to finding it among my grandmother’s stuff.

This quip is twofold—yes, I’m referring to his work on Star Wars. But also…Super 8 is masterful. It’s better than Stranger Things. Similar concept, done better. Watch it, if you haven’t. But also…Abrams and Spielberg made that movie out of nostalgia, to celebrate an experience of childhood explicitly shaped by the sci-fi movies that made Spielberg famous.

I linked this because I had it—but this was also assigned to me, and not an original idea (unlike most of my articles for GameRant). The show in question is out now—which makes it even weirder—, but truly I could write a great deal about Hawley’s work, as I revere Fargo and adore Legion.

I am leaving adaptation out of this because adaptation is as old as English-language storytelling itself (by which I basically mean Modern English storytelling, beginning with the British Empire)—simply telling old stories is so ingrained in English narrative history that I cannot say it is not a core narrative form.

Credit to Hbomberguy for this one: “Plagiarism and You(Tube)” is, of course, one of my favorite videos. If you only ever watch one video I’ve recommended, it should probably be this one.

It’s not; the Production Code was very bad for art—and, for what it’s worth, the demise of that Code was followed by what I regard as an awkward transitional period in American cinema. But that’s another post.