I Wouldn't Write The Winds of Winter, Either

...although I would at least have the good grace to admit it.

My first book series is about a fantasy world where magic is as commonplace as electricity, where the secret of a family is the vulnerability of a nation, and where the protagonist is wandering aimlessly towards fate, asking every woman she meets, “Are you my mother?” It is sprawling and lore-heavy and theme-driven. Every part of the world has been meticulously crafted around the story of this one woman, who is a stranger in her own kingdom. And the events that brought her to this story span a thousand years, involving characters with their own complex narratives (and deliberately-overcomplicated names).

I wrote the story in order, skipping nothing, during the pandemic. I have three-and-a-half books, and none of them are publication-ready. For most of the first two books, I had no idea what the big mystery was driving the main plot. I knew some things about my endgame, but I deferred working out the details until I already had a substantive story. When I finally started filling in the background…a funny thing happened. Without considering it directly, I came to understand why George R.R. Martin will never finish A Song of Ice and Fire.

Plotting vs. Pantsing

If you are a writer, you may have heard the terminology, plotter vs. pantser, before—but, please, stay with the class for the benefit of newcomers. I first encountered the terms through DSilvermint’s incredible thread on what went wrong with the finale of Game of Thrones (which I consider to be an essential text on narrative theory). In the thread, the author describes plotters as writers who “create a fairly detailed outline before they commit a single word to the page.” By contrast, DSilvermint characterizes pantsers as writers who “discover the story as they write it, often treating the first draft like one big elaborate outline.”

“…if you, as a writer, lose focus on your story, you may find it difficult to pick up the narrative and continue—”

As I mentioned in my first post for this blog, I am all about the discovery—I am a consummate pantser. I feel hampered by an outline, confounded by the task of connecting together scenes that I have already imagined. Moreover, writing from an outline lacks the same joy for me—I am as excited to find out what will happen as I wish my reader to be. This is not a superior approach (as DSilvermint notes—both approaches are valid), but it is the one that works for me.

The core pitfall of pantsing, however, is that narrative creation is easier than narrative resolution. When I am discovering my story, everything I say, no matter how offhand, becomes part of the story. In order to resolve the story, I have to track all of those threads I’ve flung and bring them together in logical ways—or choose between incompatible narrative paths. Because the chaos of a story increases as I create it, before I try to resolve the many threads, I have decided to call this effect narrative entropy.

Pantsing My Way Right Out of My Story

So once I had worked out where my series was going, I needed to communicate the relevant bits to the audience, independent of what my characters knew (which was fucking nothing). I started writing these rich, self-contained chapters, disclosing each historical character’s background as if it were its own story, with its own themes. The resulting chapters contain some of my favorite writing—possibly some of my best writing. I delighted in writing them, picking up the threads of my story and weaving them into a thematic narrative that gave weight to what I’d already crafted.

But then…I was spending an awful lot of time writing them. And I was getting more granular, telling one character’s story across days, rather than years. Again, this character was not part of my narrative heretofore—she had no stake in my protagonist’s story. Yet I wanted to know more about who she was and how she came to be involved in the present narrative—and the only way to find that out was through writing.

I backed away slowly, leaving the chapter unfinished and forcing myself to return to the main plot. I could easily see myself writing an appendix, or a short story—or a book of fables in the world of my story. I had gone down the road of worldbuilding, and it offered too many temptations for me to trust that I would find my way back, eventually, to the original narrative.

So…Is Worldbuilding the Enemy of Story?

Wtf, Ingrid?

In the ascendant days of Christopher Nolan, we seem to have lost the notion of narrative focus—and I do not have time to get into that statement1. But I will sum it up by saying that I think there is only so much worldbuilding that a narrative can use. I am haunted by the comment that was shared with me during season 1 of Westworld, positing that Westworld (the park) was located on Mars. My response at the time was, “I mean, sure, but…why?” Anything you theorize about a story, that is not supported or precluded by the text, could be true—but what would it add to the narrative?

In her excellent THE Vampire Diaries Video, youtuber Jenny Nicholson analogizes the writing process of The Vampire Diaries as, “To speak figuratively, the whole Vampire Diaries is like, the writers paint themselves into a corner, and then they realize they’ve done that, and then they’re like, ‘Whatever,’ and they just walk across the paint, ruining it.” It seems plausible to me that, the more you worldbuild without regard to the story being told, the more you risk walking over the paint. Sure, your world might be more interesting—and audiences may keep coming back for the content—, but something will be lost from the story. Jenny remarks on this narrative emptiness in The Vampire Diaries, noting that death became utterly meaningless during the run of the show, undermining the emotional weight of the (many) death scenes2.

I love worldbuilding, and I think it enriches stories of all kinds—even stories that are ostensibly set in our universe. But the story should come first. More than that, if you, as a writer, lose focus on your story, you may find it difficult to pick up the narrative and continue—especially if you, like me, feel chafed by knowing too much about where the story is going.

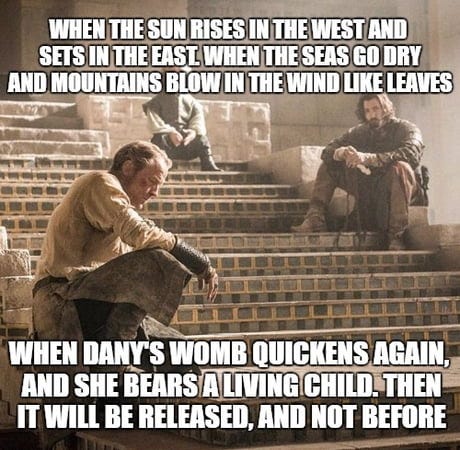

Why I Wouldn’t Finish the Book

Returning to the concept of narrative entropy, the world GRRM has built through ASOIAF is so incredibly intricate, with a thousand threads of plot and lore and character—all contributing to the chaos of the story. Add to that the further worldbuilding he has done through supplemental stories, which have only increased the narrative entropy of the series. I, personally, would struggle to pick up those threads and find a logical way to bring them to a satisfying conclusion.

Moreover, finishing the story has become a losing proposition: I would never be able to escape what I had learned about my narrative through the botched finale of Game of Thrones. I have tremendous respect for the members of r/pureasoiaf (nerds of a caliber I can only dream of approaching)—but the world they envision is already gone.

If we imagine all the possible paths our stories could take as existing in a liminal space, when one of those paths is articulated, it becomes harder to take other paths. Remember when you were a kid, and you had a crush—but it didn’t feel real until you told your friends you had a crush? I’ve noticed a similar phenomenon with story beats and details: as soon as I jot them down, I become more inclined to commit to them, regardless of other possibilities. Besides the ending enshrined in that disgraceful Game of Thrones finale, a hundred or more adjacent endings for GRRM’s saga have been realized in the discourse that followed. As an author, I would not know how to return to a story that had become so frayed.

Finally, there is victory in silence: the book series, as it currently exists, is fantastic. It is foundational to my own fantasy writing, and it has inspired countless others. By never returning to it, GRRM can take a win, in a situation where any step forward risks immeasurable losses. Maybe he knows how it ends (which I would only believe if he had worked it out before the second season of the show aired). Maybe he will tell us (in his will). But he will not finish that story.

I wouldn’t either.

In this post. ;)

Excluding the death of Bonnie’s dad—but even then, it’s the rich performance of Kat Graham that gives weight to that scene.

Solid meme game in this!