When I was in 9th grade, I took Art as my elective. My school was small and private, so electives were often limited—there was one class for every elective, and if you had availability during that period, you could take it. Moreover, the teachers who taught these electives had…varying levels of experience. No shade to my teacher (also my 8th grade English teacher, whom I loved), but I would say that the curriculum of my one and only art class was less an instructional course in how to do art and more of a guided practice through a selection of introductory media.

I really struggled with this class. I had always been creative, and my mother had introduced me to a number of paper and fiber crafts—but now I was required to produce three sketches each week (as homework), with little direction or experience. These sketches took me so long to do—as did my in-class projects, resulting in me turning in my final project (several assignments behind everyone else) during the Christmas break. Some of my output seemed competent enough, but because it took me so long to complete anything, I walked away with the distinct impression that I was not cut out to do art.

This impression was only reinforced by the one art class I took in college, a prerequisite of my visual arts major. Again, I received little instruction and was expected to complete works in a selection of media. I produced one piece of art I liked, a self-portrait in charcoal—from which I concluded that charcoal was just a medium I was naturally suited to.

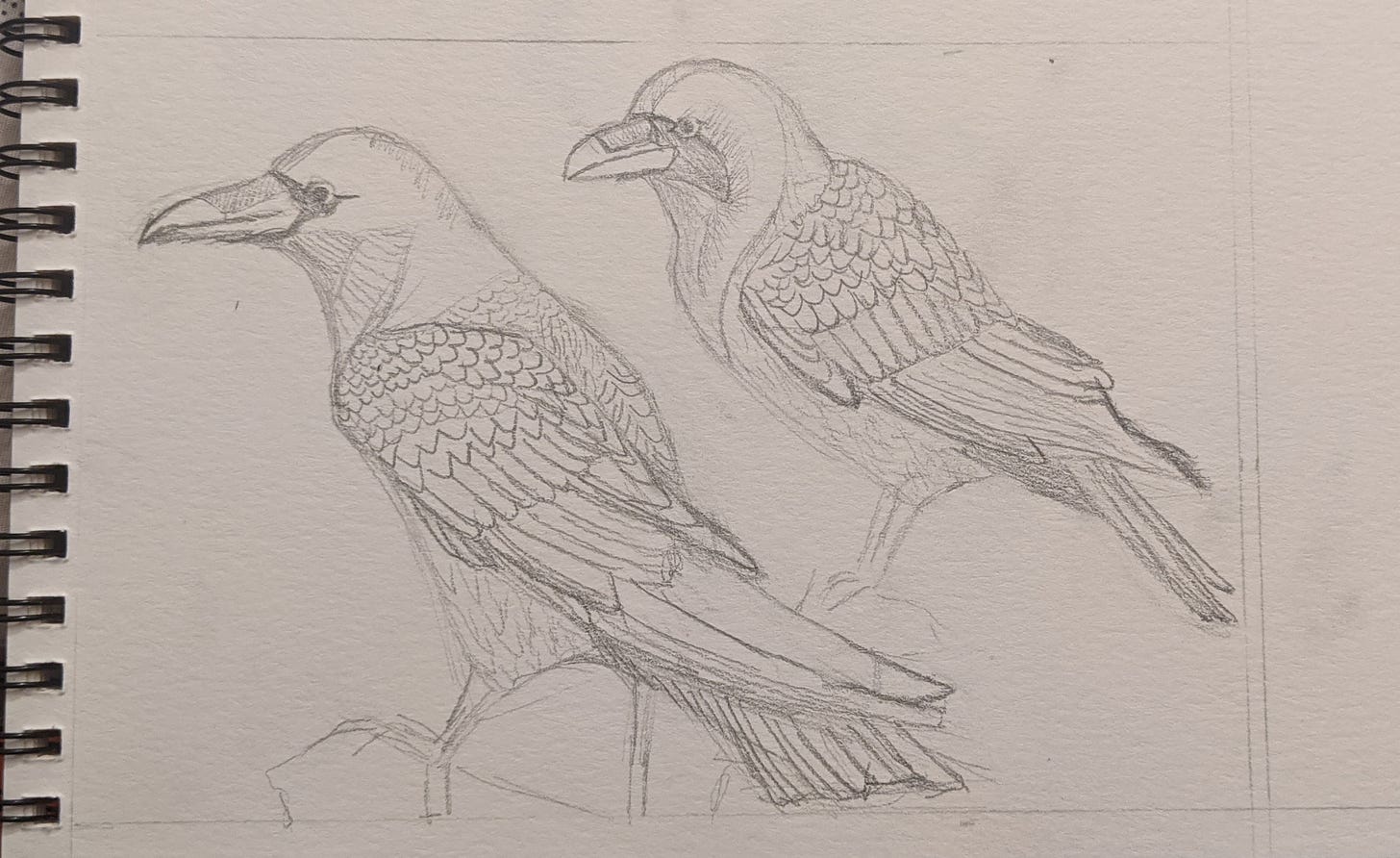

Fast forward to the pandemic. Deprived of my job for social distancing reasons, I found myself with a lot of time and a surprising amount of financial security. One day, after a dentist appointment, I wandered into the nearby art store, thinking that I could use a new sketchbook (I like to use sketchbooks for note-taking). The pandemic had enabled me to, for the first time, put my writing aspirations into practice, writing my first novel in about a month. While I was in the art store, I spied a book of blank watercolor postcards, and I had a notion to make a get-well card for a friend, who was in the hospital. I remembered that I had enjoyed watercolors in my high school art class, so I bought the book, plus a compact travel watercolor set. I went home, looked up a tutorial, and painted my first bird.

And then…I kept painting birds. And drawing birds. I bought a charcoal set, and I drew more self-portraits. I looked up tutorials, and I made color charts. The more I drew, the easier it became. I was making art. I was an artist.

The Same Thing—But Writing

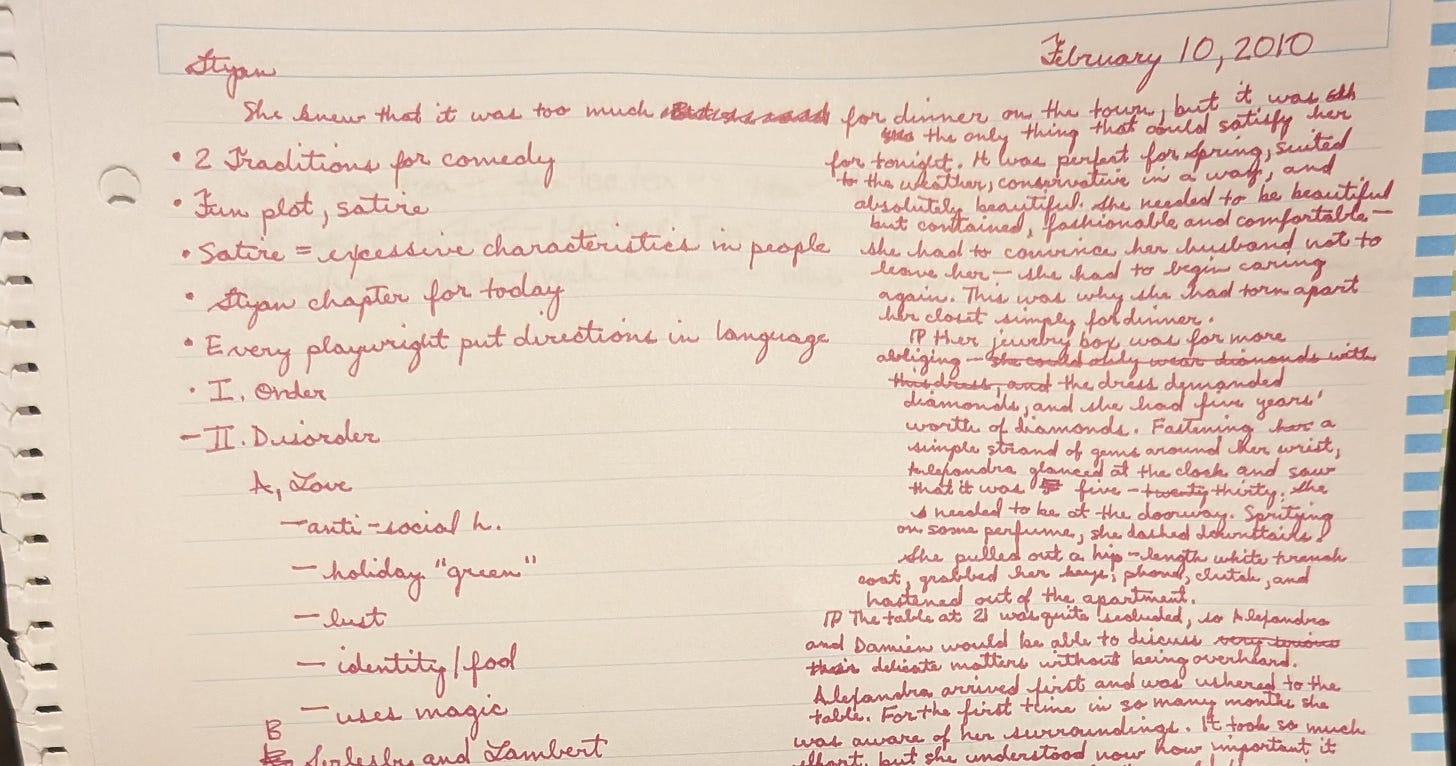

I have been making up stories since I was a kid. I relied on my imagination to keep me company, so I always had a story going, usually for weeks or months, before I would move on to the next one. I would act them out in my free time, or watch them like movies in the back of my mind whenever I was bored. Starting when I was a teen, I would scribble these stories down in the margins of my lecture notes, along with poems or random thoughts, a practice I continued through college. When I worked at Talbots, I wrote them in red ballpoint pen on the backs of order slips.

But I did not call myself a writer.

My first serious attempt at a book was in 2011, when my computer died while I was recovering from head surgery (so I couldn’t return to work). I wrote about 40,000 words on my iPhone—when I had a computer again, I put those words into Scrivener…and found a logical flaw in my story. I gave up on it.

Still, I did not call myself a writer.

I made several more unserious attempts over the years—but every time, I struggled to overcome the smallest of hurdles. In the back of my mind, I was worried about whether the effort would be “worth it”—whether what I envisioned could be completed1, or if I would ever be able to put it out into the world (something I still grapple with…but that’s another post). All the while, I continued to tell myself stories.

When the pandemic hit, I was revisiting a fantasy story that had been a perennial favorite since college. I would speak the dialogue scenes out loud while I was working as a housecleaner, and I had basically the first act worked out entirely. Then I was no longer housecleaning, and I had no idea what to do with myself. So one night, around midnight, I opened my computer and wrote 7,000 words. The next day (the same day, really, since I wrote until late morning and slept until the late afternoon), I kept going. A month later, I had a book.

Suddenly, I was a writer.

What changed? I wrote. I wrote every day, often staying up all night on binges that really activated my galaxy brain. Through the process of writing, I learned. I had always been an extremely strong writer from a language perspective—but I did not know how much I didn’t know, how much I still had to learn, which I learned solely through the act of writing. I did not stop for anything, underlining words that I thought I wanted to change, pushing past plot points that seemed shaky—trusting myself as an editor to catch elements that were weak and find better ways to tie the story together. I learned how to overcome blocks, how to examine my plot and figure out what wasn’t working—how to develop symbols and themes in ways that would be satisfying to a reader. I wrote. I was a writer.

Worldbuilding Is Not Writing

As a writer, I have been pretty online, joining Discord servers with other writers and perusing subreddits on topics adjacent to writing. One of these subreddits, with which I have a rather mercurial relationship, is r/worldbuilding. There, I found an entire subculture: people who want to be writers, but who don’t do any writing. Instead, they fill up documents and wikis with information about the worlds they imagine, independent of any stories or themes.

When you are writing a fantasy story, the world you are crafting works together with the story you are telling.

I will not say there is no value in this exercise—but I am hesitant to call the exercise “writing”. When you are writing a fantasy story, the world you are crafting works together with the story you are telling. “Winter is coming” has power because it foreshadows a final confrontation with a villain that is bigger than the petty political conflicts of Westeros. The Man in Black appears in the form of John Locke because doing so drives home the message that Locke’s personal sense of destiny was immaterial to the battle between immortal brothers. Tatooine is a nowhere planet (or at least…it used to be) because it invokes an established mythological tradition of saviors coming from lowly places.

If you build a world without regard to story elements—if you ever actually write down a story—, your story will lack the richness of these cultural touchstones, because the world will not support the story. Or, if you want to make world details support the story, you will have to revise much of the existing world—or hamstring the story, to match the world you have built. Worldbuilding is absolutely essential to fantasy stories. But worldbuilding as an exercise will not teach you how to write a story.

If You Want to Be a Writer, Write!

One post I’ve seen often, on multiple writing subreddits, is a variation on the question, “How do I start writing?” The answer is simply, write. Write down one word, then another. You will learn more from doing this than you will from reading forty books and soliciting one thousand comments’ worth of writing advice.

In the only fiction writing class I took in college, a short story writer came to speak to us one day. He had an absolutely bonkers method for writing. He writes one word, decides whether it’s the right word—then writes another word, reads both words together, and makes sure that they belong together. He revises after every word. After every sentence.

This was the worst writing advice I have ever heard2. Do not write like this. If you want to be a writer, write a bunch of words—do the revising later. If, like me, you are a perfectionist, you will struggle to continue if you are constantly worried about whether the words are right. Just put words down.

I also want to offer a tangent piece of advice: if you want to be a writer, you should read. I can often tell the difference in prose between a writer who reads and a writer who doesn’t (or a writer who only reads certain types of writing). Charles Dickens did not have subreddits to give him writing advice. People have been writing for millennia—often, with only the writing of others to teach them. Reading teaches you how to write. Read a diverse array of books, and you will be astounded how much your own voice develops. Read sonnets, and you will discover the lyrical possibilities of language. Read nonfiction, and you will learn about what makes people people, and how to craft whole people for your story. Just…read.

If You Write, You’re a Writer!

Do not be intimidated; if you write, call yourself a writer. Don’t qualify it. Tell other people you are a writer. Because you are.

After all that stuff I said about worldbuilders, I want to aver that I am staunchly anti-gatekeeping. If you write, you’re a writer. If you make art, you’re an artist. If you sing, you’re a singer. The only requirement for you to consider yourself an artist is to do your art.

As the pandemic receded, I saw some discourse happening on this topic on Twitter, and I think it’s worth addressing. You can be a writer and still have things to learn. You do not have to be “good at writing” to be a writer—but you will also get good by writing, so it’s a win-win. Do not be intimidated; if you write, call yourself a writer. Don’t qualify it. Tell other people you are a writer. Because you are.

And go into writing spaces! Find a community of other writers, and learn from them. Perhaps they will learn something from you. ;) You are not an imposter. You belong. Because you write. You’re a writer.

I cannot express this fear better than one of my favorite quotes, from Jane Eyre: “I was tormented by the contrast between my idea and my handiwork: in each case I had imagined something which I was quite powerless to realise.”

I believe he acknowledged that this was bad writing advice—or, at least, he suggested that other people should not necessarily write this way.