Before I went to college, I never wanted to watch anything “scary”. I had seen two1 thrillers in my whole life (Diabolique2 and Wait Until Dark—both of which I still recommend), and I had read one Agatha Christie novel in middle school (over the concerted objection of my mother). So I was rather horrified when, in my final year of college, my Film Authorship professor announced that we would spend a full half semester focusing on one genre: horror. Why? Two reasons. First, we stuck to one genre because it’s a good way to observe how individual filmmakers exert authorship over their works—the conventions of genre were the control, against which we could study different stylistic choices. Second, my professor chose horror because, as a genre, it has been salient across film history, with conventions that are well established.

But I am not here to talk about horror (not right now, anyway). Instead, I would like to apply that exercise to another, emergent genre…romantasy. No, don’t click away! You see, I spent 2024 throwing myself into this strange new genre, and, while it did not do much for my craft on a technical level, it had quite a bit to teach me about the craft of storytelling—of being in dialogue with your audience, and about balancing the less technical aspects of your story.

What is romantasy?

I actually intend to talk about this quite a bit, so it seems useful to establish it thoroughly right at the outset. Romantasy is a portmanteau of “romance” and “fantasy”, which may be obvious—what is less obvious is what this means, when most fantasy stories already contain ample romance.

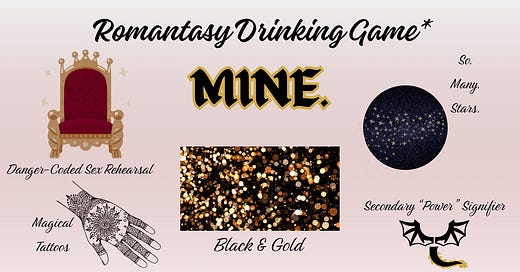

I would argue that romantasy is more of an aesthetic than a genre, although its conventions are pretty robust (not least because many authors seem to just be copying each other’s story beats). If the term ‘Reylo’ means anything to you, romantasy is that—but with fey/dragons/witches/vampires/werewolves/elves/demons. It is a dark, dangerous man and a woman who is just coming into her power; she enters his sphere and finds her ultimate power through her relationship with him. Not all romantasy is like this…but a metric f*ckton of it actually is. I eventually came to the conclusion that romantasy is, at its core, a power fantasy for straight women of a certain age (but that’s a different post).

More than a genre, romantasy is a vibe, conjured as much by the assumptions of the reader as by the story the author presents.

Priorities

You can’t do everything, as an author.

I have written three stories now, all fantasy, which total about half a million words (no, none of these books are available—because I am a perfectionist, and editing and promoting are much harder than writing). My first story (three books, so far) was theme- and character-driven, so I was focused on progressing my characters along the narrative route prescribed by theme. In other words, the arc of my narrative followed the theme, with plot points crafted to guide the reader through the statement I wished to make with the story as a whole.

When I wrote my third story, I was explicitly attempting to write a romantasy—and I quickly learned that it’s much harder to focus on symbols and character beats that support a theme when you are also tracking every sparkle of the Main Love Interest’s eyes, every craving the Main Character has to taste his blood. You can’t do everything, as an author.

It’s like that meme about college: from the choices of good grades, social life, and enough sleep, you can pick two (I did NOT pick enough sleep, for the record). When writing fiction, you can pick from characters, theme, prose, genre, and worldbuilding3—you can’t pick all of them, and if you try, all of them will suffer. This is where genre comes back in: writing within a particular genre allows the writer to bootstrap much of the worldbuilding on existing conventions. I believe this limitation also explains why several of the most popular fantasy series are based on history; writing from history is like working from a template. But the balance is perhaps most apparent in fanfiction, where using existing characters and worlds allows writers to hone other aspects of storytelling skills.

Working Backwards

As part of my semi-scientific approach, I graded the romantasy books I read last year on five metrics: Writing, Characters, World, Romance, Sex. The list I defined in the previous section evolved from the following rubric, which bears some explanation.

Writing. With romantasy, I decided to roll prose and plotting/story into one metric (in part because the prose of these books was almost universally…less than strong). The books that scored highest here had the most coherent prose and the most cohesive story arcs.

Characters. Romantasy’s conventions are perhaps most consistent when it comes to character tropes—usually the protagonist is Not Like Other Girls, and the MLI is some variation on the phrase “dark king”. Books that scored highest here featured protagonists with distinct emotional arcs and growth that felt earned and meaningful.

World. This was all the worldbuilding, which I will focus on in the next section. Books that scored highest here had worlds that were actually crafted to suit the story, with small details that made the world feel like a lived-in place (not just a mood board).

Romance. This metric refers specifically to the narrative arc of the romance plot. I will also cover this more in the next section, because the books that scored lowest here4 felt like loosely-rewritten fanfiction.

Sex. This is a critical part of romantasy—perhaps the most critical part, as the fantasy that is (often) served first by the genre is the fantasy of a fulfilling and profound sexual relationship. I graded based on whether the sexual relationship contributed to the story as a whole…and how it served the audience, as a participant in the fantasy.

Gesturing

I would like to state, unequivocally, for the record, that I do not look down upon fanfiction categorically. It is not only a valid form of writing practice, but it is also a vehicle to explore relationships in stories, without having to worry about building a world or plotting a narrative.

That said, romantasy has inherited some very bad habits from fanfiction. As I stated, the protagonists of the romantasy books I read5 were almost universally Not Like Other Girls. That was accurate—but it wasn’t precise: many of the protagonists I encountered were…Katniss Everdeen.

I love Katniss—I love The Hunger Games, actually, from start to finish (perhaps more since I wrote about the first movie for GameRant). At the beginning of her story, Katniss is prickly, determined, resourceful, and traumatized. Every explicit aspect of her character is motivated by her history and her circumstances. We understand why she is the way she is. She despises her mother because her mother was weak when Katniss needed her to be strong. Her love for her sister is both augmented and overshadowed by constant fear, that something will happen to take the only family she still trusts away. She knows how to use a bow because her father taught her.

Feyre I-Don’t-Care-to-Look-Up-Her-Last-Name’s mother was dead before Feyre needed her. Feyre hates her sisters because…they aren’t as resourceful as she is? But she has to provide for them because…she just does? And she knows how to use a bow because…she taught herself…? 👀 At the start of ACOTAR, Feyre is Katniss reconstituted—but without any of Katniss’s motivations, her traits seem illogical and unearned. Feyre just kind of…sucks.

This is how many of the characters, and much of the world, in romantasy is constructed—not through craft, but by the author gesturing to other characters or conventions, as if to say, “You know…that.” This facet of the genre undermines almost every story under its umbrella. In the absence of explanation, readers will supply their own explanations to connect elements of a story, because the human brain seeks logic. If you open a romantasy book expecting to see symbols and tropes from the same works that informed the author, you can derive meaning from what the author is gesturing to. If, however, you go in cold (or critical), you will encounter traditional narrative elements cobbled together haphazardly, with massive logical gaps strewn liberally throughout.

So…who is this for?

First, I don’t want to pass over the point I just made: for many romantasy readers, reading these books is not a critical exercise. The people who write these books have found their audience, and they are serving that audience—more so than the better writers who have ignored the same readers, and the stories those readers crave. Remember that you, as an author, can’t do everything. The series that scored lowest in my table on Characters and World also scored highest on Sex.

“…the fantasy that is (often) served first by the genre is the fantasy of a fulfilling and profound sexual relationship.”

There is a Youtuber, KrimsonRogue, whom I really like—who does book reviews, mostly of bad books. I am linking his channel because I generally agree with his analysis, and I find it instructive for my own work. But sometimes, I also find it exhausting. He is exacting in his analysis, thoroughly dissecting the weaknesses of characters, theme, prose, and worldbuilding. In the last couple of years, he has veered very much into romantasy—and it was only when I heard his analysis of a book I had read that I realized he was less thorough in highlighting the strengths of that book than its weaknesses.

I believe this imbalance was unintentional. He understood the weaknesses of the text, but, I believe, he missed the point.

The book in question is the extremely viral Fourth Wing, by Rebecca Yarros, which ranked fairly high among my romantasy reads. I scored it well because I could see what the author was trying to do—and I thought she did a half-decent job of it, considering how much plot she was actually juggling. She did far less gesturing to existing works than most romantasy and showed far more effort to construct her own world, with a solid thematic underpinning. In fact, Yarros’s greatest weakness (one KrimsonRogue does acknowledge) is trying to cram too many original details and characters and twists into her story—bloating the book with names and places and stakes that quickly lose meaning for the reader, as they are introduced too frequently and progressed too hastily.

A specific example of this problem is one of KrimsonRogue’s biggest complaints: the world of the book is predicated on a system in which students of the military college (where they learn to ride dragons—but the dragonriders are the elite fighting force of the nation, so it’s a military college) are allowed to kill each other without consequence. Krimson refers to it as the “murder college”—and he is not wrong in his excoriation of this element. It is an error of craft that is massive and glaring and kind of silly. If Yarros were telling a fantasy story, the error would be fatal.

But Yarros’s story is romantasy. It is the fantasy of a woman gaining power through her relationship with a powerful man—or, rather, about how that man uses his power to give her space while she finds power within herself. And the people who enjoy this book, myself included, do so because that fantasy is good. Sure, I thought the murder college concept was ridiculous and unsustainable—but I also understand that making it make sense was not a priority for Yarros. Her priorities were twisting the plot, actualizing the protagonist, and tracking Xaden’s shadows—all things she does effectively, delivering satisfaction enough that I was willing to overlook some messy worldbuilding.

I am not going to say Fourth Wing is good. It’s not, really. But it is not as bad as KrimsonRogue construes it…for a reader who is part of the intended audience.

I was still a kid when I realized that sometimes I liked content that was bad. At that point, I created two axes of evaluation, separating artistic merit from my personal enjoyment. As I grew up, I observed that most people don’t make the same distinction. Few things annoy me as much as seeing someone on the Internet declare that The Last Jedi was “objectively bad” (yes, I have seen this—more than once). All statements like that tell me is that the speaker doesn’t know how to recognize objective quality in film.

I will not paint Krimson with the same brush: his analysis is accurate. But, as a writer, I do find his criticisms slightly less useful, following this insight. It’s haaaaaard to keep track of all of the threads of a story—especially for someone like me, who feels stifled by too much story planning (hell, if you’ve made it this far, you may suspect that I struggle with scope creep, generally). What I have learned from all of this is to choose carefully which story elements will be most important for my intended audience, and try to stay focused on those. If some of the other things are uneven…that’s writing. Nobody does it perfectly. Because they can’t.

You can’t do everything. Just do a few things well—you will find your audience.

This is not true, exactly—but, somehow, I did not at the time count the multiple Hitchcock films I had seen. I guess I just didn’t find Notorious all that scary.

I literally just learned this, so I have to share: “[Producer-director William] Castle (1914-1977) evinced a genius for cheap but effective exploitation gimmicks that were often more engaging than the films they were employed to market. For Macabre (1958), for example, a $90,000 uncredited remake of Clouzot’s Diabolique (1955), he insured the life of every theater patron for $1,000 with Lloyd’s of London against death from fright;…” History of Narrative Film, Fourth Edition, W.W. Norton & Company, New York. 2004….[paraphrased from Crackpot: the obsessions of John Waters]. I’m so curious whether any of that citation is correct. Now. We’ll see if I even leave this in—it has so little to do with what you’ve just read and more to do with what I’m writing now. Will that be my gimmick? Am I just enamored with Junot Diaz? Who’s to say?

This is currently a working theory—I am not sure, yet, what the final form of the list will be, but I am still confident enough in my premise to include it.

I am not averse to calling out other writers, but I would like to do so with purpose and context.

There is simply not time to cover this now, but romantasy is (perhaps more than any genre before it) shaped by and dependent upon the algorithm. It is possible that I was in a particular silo of the genre seeded by ACOTAR and flowing mostly in the same vein. My ratings dataset includes seven series and two standalone novels; beyond that, I read a few other novels/series that didn’t seem worth recording. I sourced my books from friend recommendations, reddit, and goodreads—perhaps there is more diverse romantasy, but I think it’s fair to say that I consumed the most mainstream flavors of the genre.